Repost: Written by me, originally published by PEOPLink

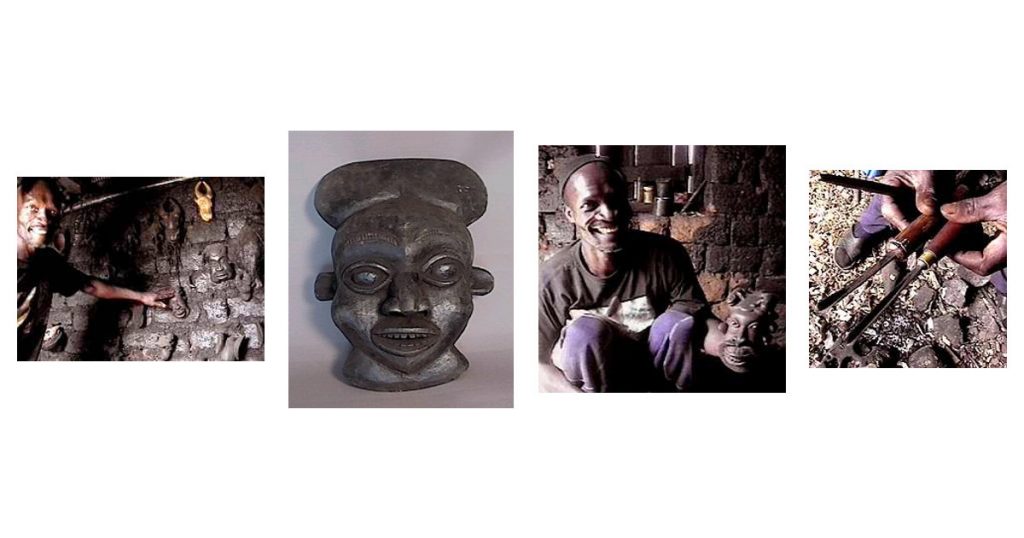

Nchinda Wanjel Frances is a traditional carver from the village of Oku in Cameroon. Most of what he produces is for traditional use in Oku — where many of his works are treated as sacred objects.

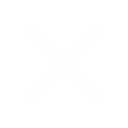

Wanjel still employs the low-tech carving traditions that he learned from his forefathers. Using only his hands, a wooden mallet, and homemade chisels, he sculpts traditional Oku masks and stools of astonishing beauty, complexity, and simplicity.

The near-perfect symmetry of his pieces is achieved without even the benefit of a ruler.

Occasionally he sells to tourists, or expatriates living in Cameroon, such as Peace Corps Volunteers. However, Wanjel’s steadiest customers are the people of Oku themselves — including the Fon (king) of Oku. They buy or barter for his masks or stools. The stools are used in the kitchen for cooking by the fire.

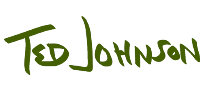

The masks become the heads of jujus for use in traditional ceremonies. A juju is best described as the representation of a traditional spirit. However “representation” is hardly the word: The people of Oku do not regard a juju as one of their neighbors dressed in a costume; they revere the juju as the spirit itself. Traditionally, women are prohibited from seeing jujus — or from even seeing the masks* when not in use.

As a traditional carver, Wanjel is particularly sensitive to the relationship between Oku and the Kilum Mountain Forest which surrounds it. He depends on the forest for various types of wood, leaves, medicine, bush meat, and honey. His knowledge of the forest and it’s traditional uses has made him an important resource to the international effort to protect it: The Kilum Mountain Forest Project.

Rather than a wood stain or paint, it is the accumulation of smoke from the fire in Wanjel’s workshop that gives his carvings their dark coloring, as well as a residual aroma.

Culture, like smoke, penetrates deeper than any superficial stain or varnish; deeper than many of us appreciate.

Wanjel, who generally wears an American tee-shirt, is nonetheless infused with the culture of Oku. The art that flows from his hands is like scent of exotic incense that takes you somewhere you have never been.

The Information Backroad

If the Internet is the “Information Superhighway” then Oku is an “Information Backroad.” No Internet. No phones. No post office. And only the well-to-do have electricity.

When PEOPLink visited Wanjel in late 1999, he had never heard of the Internet. When it was explained to him, by Edwin Fotachwi he became very interested in selling his carvings online. A system was devised for PEOPLink to communicate with him via email. It goes something like this:

- PEOPLink sends Wanjel an email that immediately reaches a mail server in Douala, Cameroon’s largest city.

- In one or two days, the message is downloaded by an e-mail service in Bamenda, a provincial capital. The message is printed out, and set aside.

- Within two weeks, a friend of Wanjel drops by the e-mail service and collects the message. He takes the message to a the “taxi park” in Bamenda where taxis and buses bound for Banso load passengers. The printed message is given to a trusted taxi driver. Once in Banso, the message may be handed again to another taxi driver who will carry the message to Oku,

- The taxi driver delivers the message to a general store that Wanjel frequents.

- When Wanjel happens to pass this general store, he will collect the message

- Wanjel waits until the afternoon when his son comes home from school so the message can be read to him.

- Wanjel dictates a response, and this entire process happens in reverse

*PEOPLink was careful to explain to Wanjel that, if his masks were to go on the Web, women all over the world would be able to see them, including women from Oku. Wanjel explained that the prohibition applies only to Oku women viewing the physical masks while they are within Oku territory

One thought on Nchinda Wanjel Frances: Traditional Carver, Oku Cameroon

Pingback: Edwin Fotachwi: Traditional Carver, Bali-Nyonga Cameroon - Ted Johnson